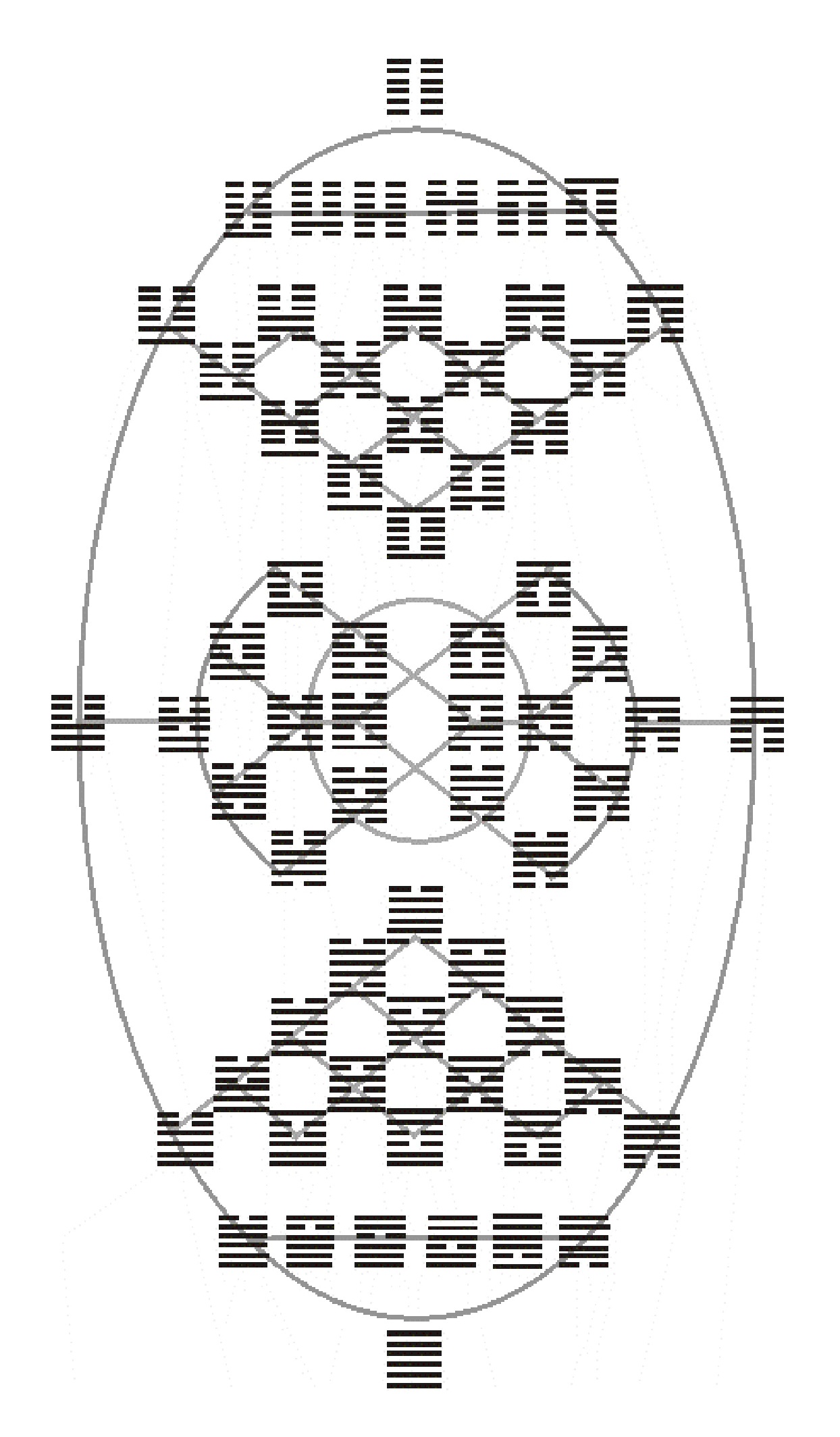

The Mandala of Changes is the symbolic representation of an orderly arranged mathematical system.

The principle that led me to the conception of the Mandala of Changes is the hexagram. The hexagram is a mathematical code discovered by the Chinese five thousand years ago. From the hexagram they conceived the Book of Changes or I Ching.

The hexagram is made up of six lines that can be whole or divided. The combination of broken or whole lines form sixty-four hexagrams, which exhaust all combinatorial possibilities, a system of interconnected and logically ordered signs.

It is the law of enantiodromia, the law of Heraclitus, that when things have reached their culmination they are transformed into their own opposite. That is the teaching of the I Ching. ~Carl Jung

The relationship between subject and object is expressed in twelve stages. Starting from the state of rest, the subject begins to search based on the need for the object. The second stage is the planning of how to achieve the object, that is, the intention. From the intention arises the action itself; the visible movement towards the object. The fourth stage is that of the power or will to appropriate the object. The fifth transformation is the resolution that involves taking the object. The sixth transformation involves the union between subject and object. In the seventh transformation, the subject assimilates the object, that is, uses the object to his advantage. The eighth transformation implies the use of what the object ceded to the subject, which implies a duty. Duty leads to production, that is, the formation of a new object. In the tenth transformation, the subject tries to separate itself from the object produced, which it achieves by eliminating it in the eleventh stage. And it returns to the resting state. These movements give rise to the cycle of transformations of being. Increase and decrease, beginning and end are consumed in twelve stages, like the day in its twelve double hours, or the year in its twelve months; or the movement of a life between birth and death

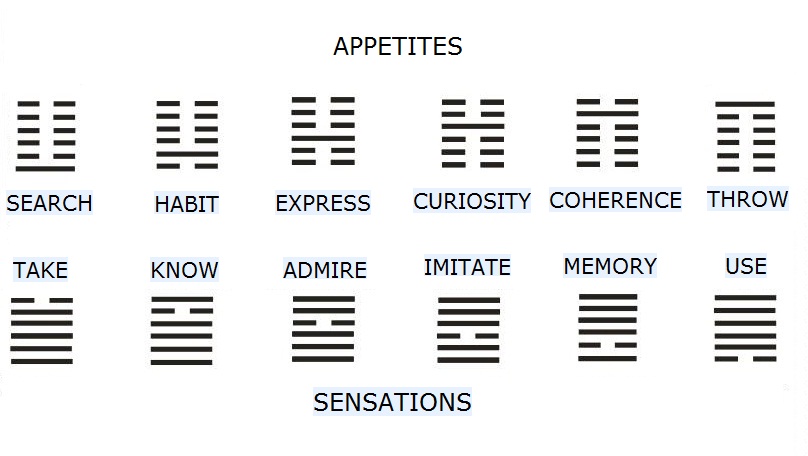

In the Mandala of Changes, the hexagrams formed by five whole lines and a broken line correspond to the sensations, the broken line being the one that bases the hexagram, or five broken lines and a whole line, which bases the hexagram.

The faculties of the body can be differentiated into appetites and affections. How we push ourselves to the objects we need and how the objects necessarily affect us. If the body receives what it needs, it will feel well-being, while if it does not receive it, it will feel unwell. The movement of the body provokes sensations in the soul. On the physical plane, the first sensation is appetite, hunger leads us to search. This search has its correlation on a psychological level in the things we undertake as people. Searching, generating habits, being able to express ourselves, the curiosity that leads us to explore, the experience of the self that gives coherence to the information we receive and, finally, how we discard what does not serve us, mark our capacities. Basic capabilities for sustaining life. The same happens with affections, that is, how we react to what the world proposes.

Just as the first thing the newborn looks for is food, the soul also needs to be nourished. This is the primary motivation that will develop throughout life. We are subject to search. Then you have to have the ability to take what was found. What was ingested must be assimilated, we must be able to use the energy that food gives us. Finally you have to throw away what is useless. We could call the movement of these four hexagrams: nourishing foundation of the soul. We will now consider another cycle of four hexagrams that represents the referential foundation of the soul. The soul needs to build an image of the environment, to achieve this it has the ability to know and remember. It must form a habit and provide meaning, that is, give coherence to the information it receives. The remaining four hexagrams also form a cycle: the cycle of the foundation of learning. These are on the side of capabilities, imitate and admire, and, on the side of appetites, curiosity and expressing.

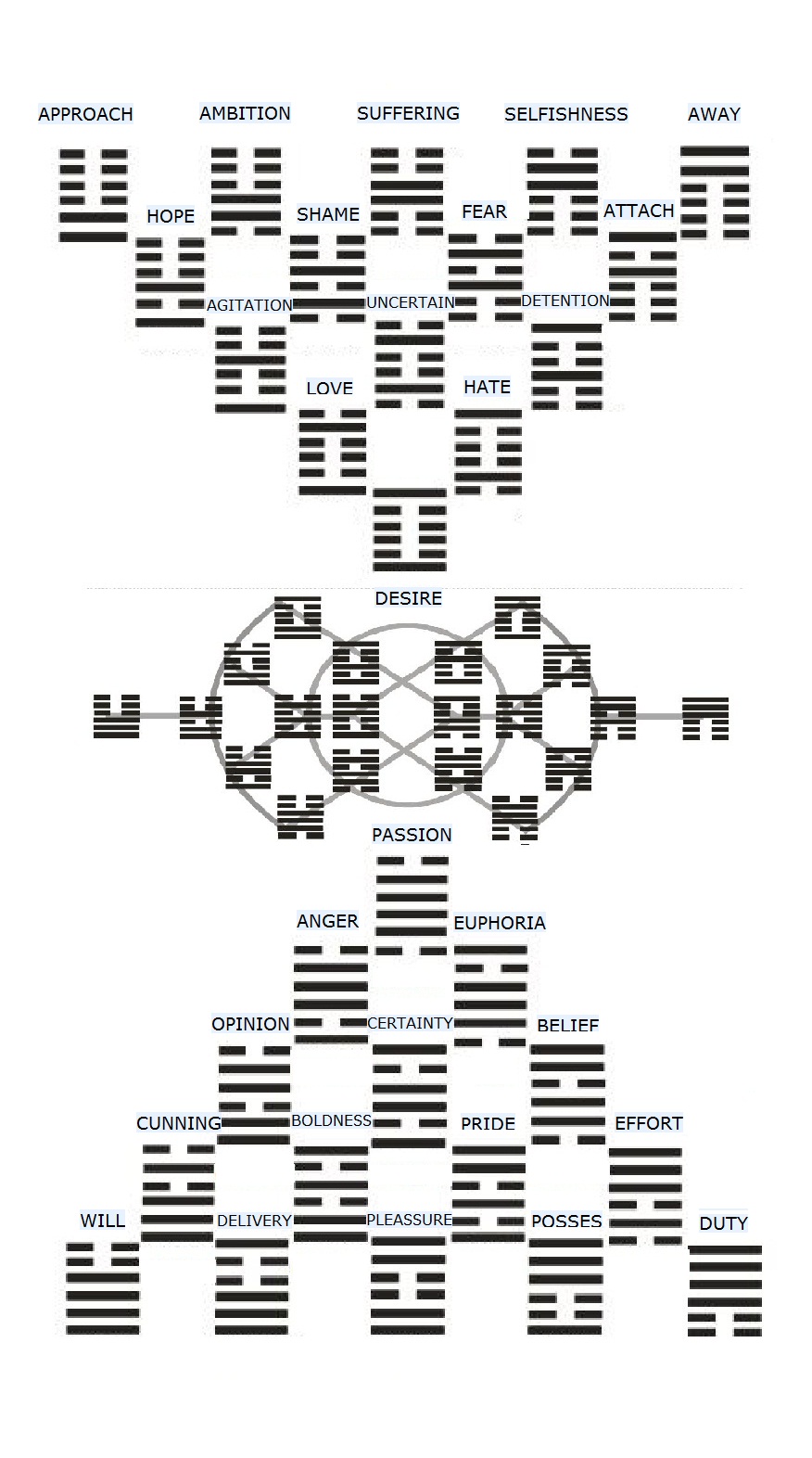

In the Mandala of Changes, the actions correspond to the hexagrams formed by four whole lines and two broken lines, which denotes an excess, or four broken lines and two whole lines, which denotes a lack.

In our performances sometimes we commit excesses, sometimes, it is not enough. Desires and passions provide us with actions that lead us to experience joys and sorrows, successes and failures. Desires reveal our shortcomings while passions reveal excesses.

Performances are the acts of the person. The term persona comes from Latin and means: "actor's mask". Joy and sadness are the masks that symbolize the theater. Social life is the stage where souls act. As circumstances require, forceful action is sometimes propitious; sometimes success is achieved when you get what you lack. This causes joy in the soul. Other times, both overperformance and weak performance can be a cause for sadness. Four acts support the relationship between people: approaching and moving away show the intention; power and duty justify the act. Six emotions are the axis of the performance: passion and desire, certainty and uncertainty, joy and suffering. Between possession and surrender lies joy. On either side of suffering are ambition and selfishness. On both sides of certainty stand opinion and belief. Between agitation and arrest lies uncertainty. When passion deviates, anger and euphoria appear. Love and hate are deviations of desire.

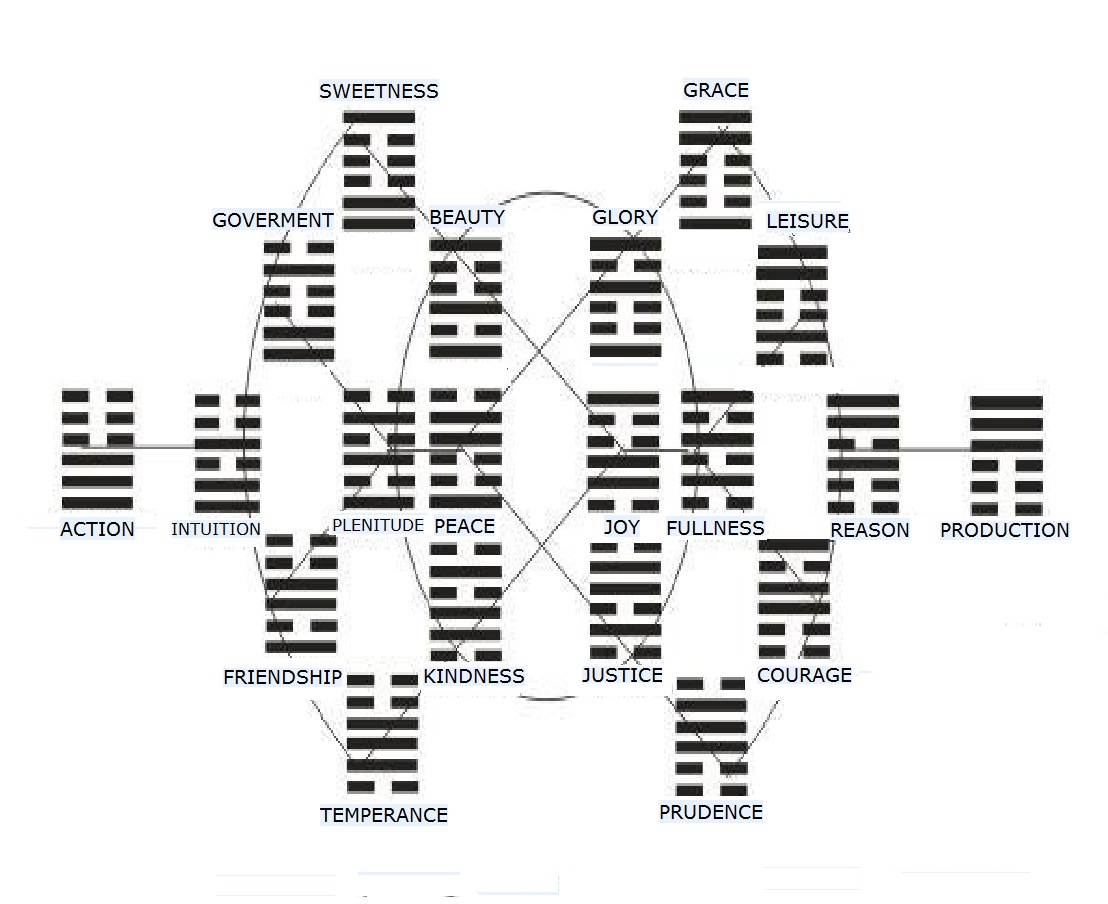

In the Mandala of Changes the hexagrams formed by the same number of whole and broken lines correspond to the virtues, and are distributed around the center of the mandala. It is the hexagrams that are in balance. Aristotle said: “moral virtue involves the passions and acts of man, and it is in our acts and in our passions that sometimes the excess, sometimes the defect, sometimes the average is produced.] [In the feelings of pleasure and pain, the more and the less meet, and none of these contrary feelings are good. But the means, and the perfection that can only be found in virtue, consists in knowing how to put them to the test as appropriate, according to circumstances, according to things, according to people, according to the cause, and knowing how to maintain the true measure in them. For passions and acts, excess in abundance is a fault; the excess in lack is likewise reprehensible; only the middle term is worthy of praise, because only it is found in the exact and just measure, and these two conditions constitute the privilege of virtue. In such a way that virtue is a kind of means, since the means is the end that it constantly seeks. Virtue is achieved through learning and habit. Virtuous acts are the result of the transformation of the soul, from animal to spiritual. In virtue, the human being expresses the set of moral rules that he has. The result of the exercise of virtue is wisdom. In virtuous acts the best of life is manifested. And it allows us to achieve happiness.